I’ve noticed an increasing obsession in product management circles on the creation and maintenance of artifacts. I recently read a LinkedIn post from Janna Bastow, co-founder of ProdPad, with a “definitive list” of product documentation that PMs are presumably meant to be responsible for:

There are also more books than ever on creating artifacts, such as the one I reviewed recently from Marcelo Calbucci about the PR/FAQ. And, of course, there are ever more tools, particularly AI tools like ChatPRD that purportedly make the PM’s job easier by having LLMs generate documents. The promise is that PMs can spend more time speaking with customers and less time writing documents.

There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with writing documents per se. A well-crafted product brief or PR/FAQ can rapidly create clarity and alignment in a team, or drive rapid decision making. But we seem to have entered a new era of artifact fetishism in product management, where the production and management of a great quantity of artifacts (the outputs) is being used as a poor substitute for the messiness of true collaboration, from which actual innovation originates (the outcomes). The creation of yet another spec has never been the sole determinant of product success or failure. Yet we seem to increasingly be treating artifacts in this way, even though much innovation over the centuries occurred without anyone writing a PRD. We need to put a stop to this practice.

Artifacts Should Represent an Understanding That Already Exists

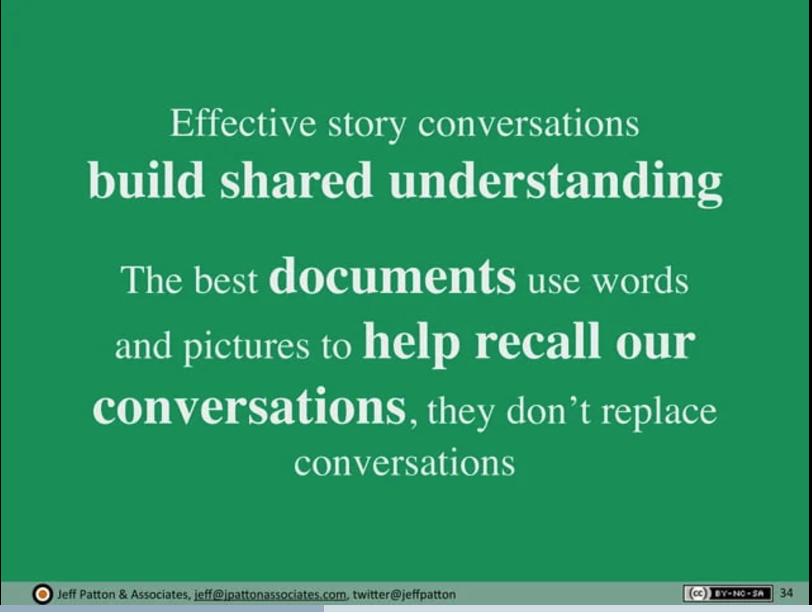

Years ago, Jeff Patton included a slide in one of his presentations exhorting product managers to use documents to represent the outcomes of conversations, rather than to replace conversations. The messy work of interviewing customers, showing them rough concepts and prototypes, weighing trade-offs with your design and engineering counterparts and aligning on next steps with them, etc. is the hard work of product development. It’s not always clean, crisp, and confident when it’s being conducted, but it doesn’t need to be. What’s important is the team’s creative synthesis of all these inputs and the learning that comes out of it to drive the product’s evolution.

PM’s job is to create clarity out of ambiguity, but not by throwing their hypotheses over the wall at partners. Documents shouldn’t be weaponized as top-down tools to “tell engineering what to do”; the most powerful innovations come from collaboration among cross-functional peers that have a healthy respect for each other. This requires actually talking to each another, not just issuing memos. Unfortunately, LLM-driven tools can do a very good job of taking half-baked ideas and turning them into documents that fool us into believing they are well-validated, promising ideas, complete with reasonable-sounding success metrics. But LLMs are just parrots: trained on the corpus of all of the world’s public PRDs, they mimic written communication patterns without actually understanding anything about what they are saying.

I have always recommended to product teams that the PRD or PR/FAQ is almost the last thing you should write, after you’ve done the hard work of actually talking to customers and peers, figuring out all the tradeoffs and what to do. Not the first. (It’s ok to have early drafts in your back pocket if it helps to clarify your own thinking or to workshop ideas with peers.)

Documentation Should Have a Purpose. Look for Opportunities to Write Fewer Documents.

Many documents simply do not need to be written and certainly do not need to be perfect. Additional polishing of items on that product marketing “bill of materials” is not going to result in the difference between a product being successful or not. Now while I’m not advocating that PMs be reckless and write down nothing, I do wish that we were far more judicious in how we spend our time on artifact creation. We should ask ourselves tough questions about each type of document we are asked to create or maintain:

- What clarity will this document create, and for whom?

- How long will that clarity last (e.g. is it to drive an investment decision, or is it an evergreen record of product development?) Have I calibrated the effort I am putting into this document appropriately so that I am not needlessly spending time polishing a diamond that doesn’t need to be polished?

- Has past usage of this document type (or its format) created high ROI in terms of improving clarity and understanding?

- What would happen if I didn’t create this document? Is it possible that an adequate understanding and/or alignment with my peers could be created even without writing it?

Documents should not be created purely as a defensive mechanism against cross-functional partners. Too often, I have seen environments where documents are used as ammunition: for example, sales insists on more and more artifacts being created and perfected before a product or feature can get launched, and it’s a “blocker” if exact specifications are missing from such documents. This is an absurd standard for all but the most critical launches at a company, and highlights a more fundamental problem: lack of trust between peer functions. No additional documentation will fix that, so this is what should get addressed first to save everybody time and energy, not to mention creating a more humane environment for everyone involved.

More Operational Documentation Will Not Solve Your Pressing Business Problems

I’ll close with a set of potentially controversial comments about operational documentation, as distinct from product development artifacts. I have worked for numerous organizations in my career which had critical, existential business problems — but you wouldn’t know it by the volume of MBR reports, QBR decks, weekly status reports, detailed capacity planning spreadsheets with twenty columns of metadata, V2MOM/OKR grids, and the like that were floating around the company. It was almost like leadership teams were using the volume of documentation, and the associated man-hours needed to assemble them, as insulating material, hoping that more artifacts would magically help them solve the pressing challenges in front of them. John Cutler recently satirized this on LinkedIn.

Less is often more when it comes to documentation, and this is particularly true when it comes to documents needed to run the business. Every hour spent creating operational documentation is another hour not spent innovating. Excessive operational reporting also clouds a management team’s understanding of what (small number of) goals are important for the business, because it paints the picture that everything is important, and we all know, when everything is important, nothing is important.

It is high time that product leaders and executives alike took a much more critical eye to the paperwork burden being applied to product teams large and small. More generative AI won’t solve this problem; it will only accelerate the generation of pleasant-sounding BS. Why not just get rid of the BS in the first place?