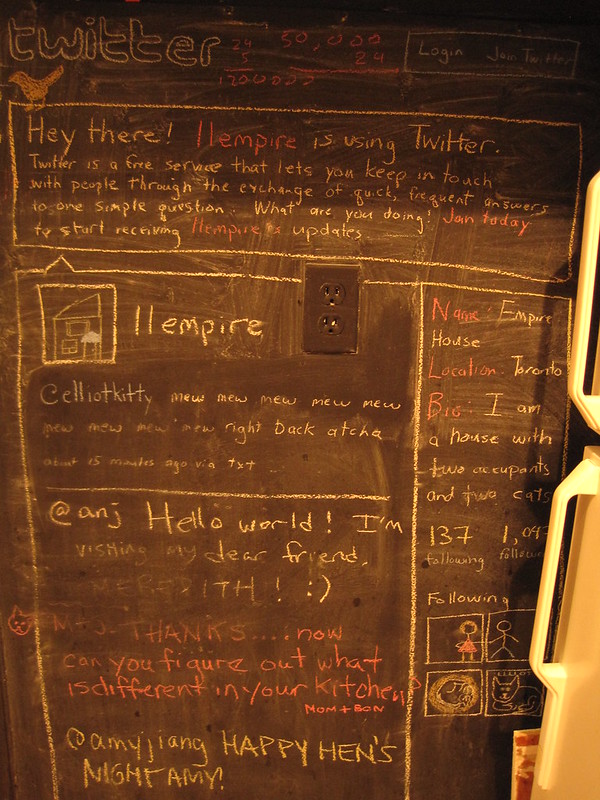

In the spring of 2009, I created my first Twitter account. To be completely honest, I didn’t understand Twitter’s utility at first, having previously ridiculed my wife, the early adopter, for wasting time on a tool purpose-built for oversharing-by-text-message. (Remember when you could post to Twitter by texting TWTTR on your phone?) I eventually came to perceive some value in Twitter, though I’m not entirely sure why I got hooked on it even though I had few people to connect to. Perhaps it was because I’d been keeping a blog in some form since 2000 or so (you’re reading it) and so I was more comfortable putting thoughts out onto the Internet with little expectation of response or engagement? Either way, Meredith and I loved the tool so much that we eventually turned our kitchen blackboard wall into a miniature version of Twitter, giving the house an “account” and using the Tweet format to leave messages for one another, as well as imagining observations the house would make if it could. (Mostly about the cats.)

I only really started using Twitter in earnest in the early days of the DevOps movement. After I’d dropped out of journalism school, I started working as a systems engineer for a startup in New York during the period when “systems administrators” were trying to find a more humane, equitable way of doing operations. Twitter was a way to find my people – folks who shared the same points of view and had a place to trade advice on dealing not only with the enormous technological change management required for this different approach, but the cultural dimensions to it as well. I continued to lean on DevOps Twitter for that sense of community after I took a job at Chef and evolved my role from consultant & evangelist into product management.

But beginning in the mid-2010’s, I felt that Twitter was already taking a turn for the worse. Not the product but the way its constituents were utilizing the medium. Its users, even within the confines of the DevOps community, seemingly started to engage in threads with a much more absolutist approach. People seemed to be more interested in defending their own points of view to the death rather than truly engaging with others and potentially changing views. The era of “that’s a good point” or “I hadn’t considered that, thanks for the insight” seemed to be coming to an end. It was around this time that I started using Twitter less and less, as it and other social media tools became vectors of increasing polarization and extremism.

Maurice Mitchell, in his excellent November essay Building Resilient Organizations, has remarked on social media thus:

[Social media platforms] reward us for our ability to articulate or reshare the sharpest, pithiest, pettiest, most polemic, or most engaging ‘content’. There is no premium on nuance, accuracy, and context. There is little room for low-ego information sharing or curious and grounded political education. These platforms are ideal for, and give immediate reward to, uninformed cherry-picking, self-aggrandizement, competition, and conflict.

Maurice Mitchell, Building Resilient Organizations, The Forge – November 29, 2022

While this is true today, Twitter and other platforms like it weren’t always this way. For better or for worse, Twitter, aside from a few largely immaterial changes, was and is still the same product it has been since 2009. But something has shifted in our norms and behaviors, and the toxicity that is often unfairly placed at Twitter’s feet is a symptom of broader social unrest, be that about racial justice, gender rights, economic inequality, or whatever. It also means that Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter and the path he has set it on with his reckless moves have only really accelerated the platform’s irrelevance and hastened its death. He isn’t the arsonist, but he is the “firefighter” who’s pouring kerosene instead of water on the flames.

Which brings me to Mastodon and how I’m highly skeptical that a product – decentralized as it is, with its individual fiefdoms – is going to provide a platform that fundamentally changes the way we engage with one another. Given that the software is essentially a Twitter clone, it has the same unhealthy habit-forming loops that Twitter does and incentivizes an always-on engagement model, which fuels the same “uninformed cherry-picking, self-aggrandizement, competition, and conflict” that Mitchell rightly criticizes. I’m uncomfortable substituting the time I used to waste on Twitter every day, looking for the drama du jour, with the same habits on another, virtually identical platform. That’s why I’ve set up a couple Mastodon accounts but I haven’t used them – and I’m not sure that I’m going to.

My old colleague from my days at Chef, Charles Johnson, recently wrote a brilliant article about this being a “lights out” moment for Twitter. For those Twitter employees who have poured an unbelievable amount of their working life (and then some) into the company and its product, it is undeniably heartbreaking to see the company suddenly moved into its twilight years. And it’s a hard lesson to learn for tech workers who haven’t yet, in their careers, experienced the capricious nature of the industry’s rapid boom and bust cycles. Yet this is a moment unlike others. 5G substitutes for 4G. Kubernetes substituted for Chef. Should Mastodon and other Twitter clones really substitute for Twitter? Or is this really the end of the road for microblogging and this model of engaging with one another?